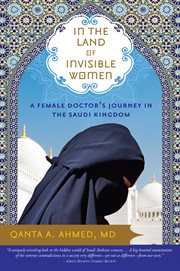

In the land of invisible women A female doctor's journey in the Saudi Kingdom

eBook - 2008

In this stunningly written book, a Western trained Muslim doctor brings alive what it means for a woman to live in the Saudi Kingdom. The decisions that change your life are often the most impulsive ones. Unexpectedly denied a visa to remain in the United States, Qanta Ahmed, a young British Muslim doctor, becomes an outcast in motion. On a whim, she accepts an exciting position in Saudi Arabia. This is not just a new job; this is a chance at adventure in an exotic land she thinks she understands, a place she hopes she will belong. What she discovers is vastly different. The Kingdom is a world apart, a land of unparralled contrast. She finds rejection and scorn in the places she believed would most embrace her, but also humor, honesty, loya...lty and love. And for Qanta, more than anything, it is a land of opportunity. A place where she discovers what it takes for one woman to recreate herself in the land of invisible women.

- Subjects

- Published

-

[United States] :

Sourcebooks Inc

2008.

- Language

- English

- Corporate Author

- Main Author

- Corporate Author

- Online Access

- Instantly available on hoopla.

Cover image - Physical Description

- 1 online resource

- Format

- Mode of access: World Wide Web.

- ISBN

- 9781402220036

- Access

- AVAILABLE FOR USE ONLY BY IOWA CITY AND RESIDENTS OF THE CONTRACTING GOVERNMENTS OF JOHNSON COUNTY, UNIVERSITY HEIGHTS, HILLS, AND LONE TREE (IA).

Review by Publisher's Weekly Review

Review by Kirkus Book Review

Her torso was uncovered in anticipation.. Another physician sterilized the berry brown skin with swathes of iodine. A mundane procedure I had performed countless times, in Saudi Arabia it made for a starling scene. I looked up from the sterilized field which was quickly submerging the Bedouin body under a disposable sea of blue. Her face remained enshrouded in a black scarf, as if she was out in a market scurrying through a crowd of loitering men. I was astounded.

Behind the curtain, a family member hovered, the dutiful son. Intermittently, he peered at us . He was obviously worrying, I decided, as I watched his slim brown fingers rapidly manipulating a rosary. He was probably concerned about the insertion of the central line, I thought, just like any other caring family member.

Every now and again, he signaled vigorously, rapidly talking in Arabic to instruct the nurse. I wondered what he was asking about and how he could know if we were at a crucial step in the procedure. Everything was going smoothly; in fact soon the jugular would be cannulated. We were almost finished. What could be troubling him?

Through my dullness, eventually, I noticed a clue. Each time the physician's sleeve touched the patient's veil, and the veil slipped, the son burst out in a flurry of anxiety. Perhaps all of nineteen, the son was instructing the nurse to cover the patient's face, all the while painfully averting his uninitiated gaze away from his mother's fully exposed torso, revealing possibly the first breasts he may have seen.

I wondered about the lengths to which the son continued to veil his mother, even when she was gravely ill. Couldn't he see it was the least important thing for her now at this time, when her life could ebb away at any point? Didn't he know God was Merciful, tolerant and understanding and would never quibble over the wearing of a veil in such circumstances, or I doubted, any circumstances?

Somehow I assumed the veil was mandated by the son, but perhaps I was wrong about that as well. Already, I was finding myself wildly ignorant in this country. Perhaps the patient herself would be furious if her modesty was unveiled when she was powerless to resist. Nothing was clear to me other than veiling was essential, inescapable, even for a dying woman. This was the way of the new world in which I was now confined. For now, and the next two years, I would see many things I couldn't understand. I was now a stranger in the Kingdom. Excerpted from In the Land of Invisible Women by Qanta A. Ahmed All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.