Review by New York Times Review

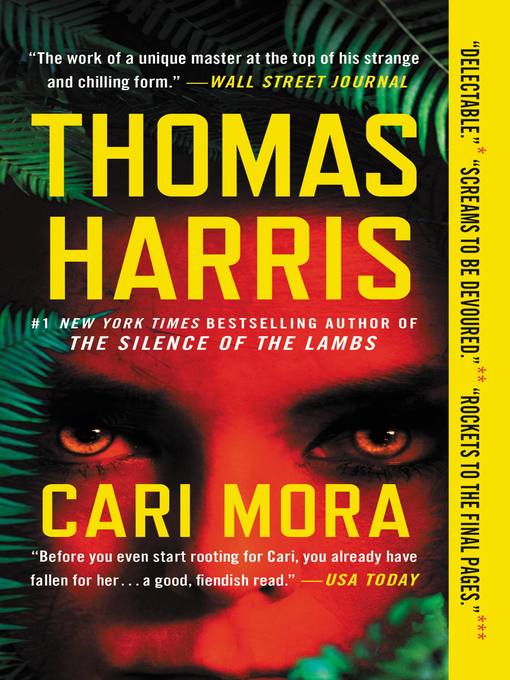

It is perhaps not a major publishing plot twist that, almost two years after the #MeToo movement burst into public consciousness and began to change the conversation around gender, power and who gets a seat at what table; a year and a half after women in pop culture, sports and Hollywood began speaking up about equal opportunity; and at a time when there are more women in Congress than ever before, proving they can be just as belligerent and forceful as their male colleagues, the traditionally male-dominated world of the thriller has been ceding ground to a different kind of hero(ine). For so long, after all, the most chart-busting thriller novels were the province of the robotic but moral special ops guy, the dissolute unshaven detective, the beefy brawler with a soul. For so long the ads in the subways and in newspapers touted boldface names like Jack Reacher, Gabriel Allon and Harry Bosch. Even J.K. Rowling adopted a male pseudonym, Robert Galbraith, to write her post-Potter adult thriller series, which centers on a disabled male private eye called Cormoran Strike. There have always been exceptions to this rule, of course - women who broke through and became part of the canon, like Agatha Christie's Miss Marple and Patricia Cornwell's Kay Scarpetta. But they were the minority, at least until the Girl books, Gillian Flynn's "Gone Girl" (in 2012) and Paula Hawkins's "The Girl on the Train" (2015). Since then the movement has turned into a bona fide trend, and plenty of authors are riding the wave into summer. Some of the women at the heart of these books are old, some young (some very young); some educated, some not; some violent, some not; and some more fully, and convincingly, rendered than others. They're as varied and unpredictable, as compelling and flawed, as women in the real world. The sheer fact that one of the most anticipated of them, the first book from Thomas "Silence of the Lambs" Harris in almost 13 years, is called cari MORA (Grand Central, $29) after its 25-year-old mysteriously competent and self-contained female main character pretty much says it all. Caridad Mora is a Colombian refugee, a child soldier survivor with blood and death in her past who now lives with her aunt's family in Miami, works at a bird and small animal refuge, and moonlights as the caretaker for a mansion once owned by Pablo Escobar. She is delectable, in both the traditional and Harris sense of the term (meaning actually edible), as well as smart and tough and emotionally and physically scarred, all of which makes her a worthy adversary for the various monsters Harris stews in the Southern Florida soup. The worst of these is Hans-Peter Schneider, a hairless fetus of a man with the requisite Harrisian tastes and a liquid cremation machine. His path collides with Cari's when the interests of two South American criminal organizations converge on her mansion in search of an Escobar legacy. Machine gun mayhem ensues. No character is guilt-free, and they reek of a moral ambiguity that is mirrored in the sense of place Harris creates. That makes them more interesting (except Hans-Peter, whose gruesomeness reads as more dutiful than shocking at this stage in the author's career). Especially Cari Mora herself, whose special skills and ability to ignore introspection derive from her own painful history, and who proves a woman to chew on. Metaphorically speaking, of course. she's tougher than she first appears, as is Sophia Weber, the lawyer at the center of beyond all reasonable doubt (Other Press, paper, $16.99), a somewhat arid, if absorbing, legal thriller from the Swedish writer Malin Persson Giolito that's translated by Rachel Willson-Broyles. It pivots on the question: If a bad person is accused of a crime he did not commit, is justice for the accused the same thing as justice for society? Sophia wrestles with the issue after a former professor brings her the case of Stig Ahlin, a doctor who has been imprisoned for years for brutally molesting and then stabbing a 15-year-old girl. Painted during his trial as a monster who, rumor had it, abused his own 4-year-old daughter, and convicted immediately in the court of public opinion, he has always protested his innocence. On examining the evidence from his trial, Sophia is inclined to believe that the law was not entirely served. Most of her friends and family (and partners), however, are not so convinced and Sophia is left largely to her own intellectual and emotional reserves, which are not limitless. She is troubled by insecurity, making her quest less like a march to righteousness than a battle that no one entirely wins, whatever the outcome in court. It is both a strength and a frustration of "Beyond All Reasonable Doubt" that the author does not feel the imperative to explain too much or to tie her ending up in a neat bow. Instead, while by the end of the book the central question has been answered, even more have been posed - and not in the way that sets up a sequel (though that could happen), but in the way that imitates life, in all its messiness and obfuscation. You kind of want to throw it against a wall. And you want to meet Sophia Weber again. If sophia is forced to separate her emotions from her work, however - her distaste for her client from her obligation to him - the parents at the heart of a nearly normal FAMILY (Celadon Books, $26.99), another Swedish legal thriller, don't even try. M.T. Edvardsson's page-turner, which is also translated by Rachel Willson-Broyles, is told in three parts, three voices and three perspectives, one for each member of the titular family, and it peels away the compromises we make with ourselves to be the people we believe our beloveds expect, revealing just how flimsy those pretenses can be. This isn't exactly a surprise when it comes to teenagers such as 17-year-old Stella, who is much more volatile and complicated than her parents want to admit (also more engaging), and who is accused of murder as the book begins. Her story is sandwiched by those of her parents: her father, a pastor and something of a weak link who spends a lot of time bemoaning the choices between God and loved ones, and her mother, a buttoned-up criminal lawyer. Their professions heighten the stakes in a muddy story of good and evil. As each family member chronicles his or her side of the situation, the Rashomon-like prism of expectations and assumptions builds to a blunt-edged revelation, one where the ability to face danger, and family, without illusion comes from the least expected place, and there is no room for existential angst about the angels of our better nature. Another child, an even younger one - Dolly, 7 - is the narrator of Michelle Sacks's all the lost things (Little, Brown, $27), a slim road trip into mystery firmly in the vein of Emma Donoghue's "Room," with all the magical mundanity that implies. Precocious, with an advanced vocabulary, Dolly wakes one morning to find her father is taking her on a drive away from her home in Queens. Bringing only her favorite toy, a plastic horse called Clemesta who serves as a kind of Jiminy Cricket to her Pinocchio, she hops into the car, but the farther they get from home, the clearer it becomes that perhaps the trip, and her father, are not exactly what they seem. Using the illogical chronology of childhood, where ignorance is the status quo and all knowledge, whether of ice cream or tragedy, qualifies as discovery, the road south itself becomes a metaphor for a highway into the past, complete with detours and potholes and danger signs ignored. It's a risky technique to place such adult issues in the hands of a child; not every grown-up reader wants to spend a couple of hundred pages in the mind of a kid, a character who can easily become cloying and fall into the category of plot device as opposed to real person. But Dolly is a funny and surprisingly substantive little girl, and an acute observer of human behavior (though the author's tendency to have her speak in capital letters as a signal of her age, an affectation that was more successful in "Room," here is largely annoying and unnecessary). At the end, when she has to face the tragedy that started it all, it's not exactly a surprise, but it is still surprisingly emotional. Dolly has inner resources she did not know existed, like Lily, the protagonist of into the jungle (Scout Press, $27), a hardscrabble 19-year-old refugee from the foster care system who answers an ad for a teaching job in Bolivia that turns out to be a scam, leaving her to scavenge work and food and friends on her own in Cochabamba. She does so, along the way meeting Omar, a local motorcycle repairman who was raised in the Amazon rain forest. She falls for both his self-possession and his ability to introduce her to a feral baby sloth (yes, that's a seduction technique); when his brother shows up to tell him his nephew was eaten by a jaguar, and he needs to return to their village to join the hunt, Lily decides to go with him. And that's just the setup. Erica Ferencik paints a picture of a jungle ripe with the amorality of nature, where dropping one's guard or losing focus means death from any number of sources - enormous water snakes or minute poisonous frogs or flesh-eating parasites - and the humans, be they gun-toting poachers or antagonistic villagers, are actually the least frightening forms of life. Indeed, the ripening natural horrors are by far the most compelling characters in the book; neither Lily nor the men and women who surround, ignore, help and threaten her (including an ancient witch with telepathic powers) can quite match the jungle's vivid danger. The real thrill of the novel lies in the question of how Lily - physically frail, but with the strength born of the stubborn refusal to give in or give up - will make it through each day, as opposed to the nominal plot, which has to do with different interest groups on the hunt for a hidden mahogany forest. Just as the real question of the book is what "civilization" actually means. As the greenery flowers and bursts and rots from within so, too, does the prose, culminating in a clash of birth, death and fluids of all kinds. Even more overheated, however, at least metaphorically speaking, is Lauren Acampora's the paper wasp (Grove, $26). Take "The Talented Mr. Ripley," cross it with "Suspiria," add a dash of "La La Land" and mix it all at midnight and this arty psychological stalker novel is what might result. Abby Graven, an anxiety-ridden 20-something, once the smartest girl in her high school class, now given to vivid dreams that she believes foretell the future and that she captures in the form of fevered drawings, has become practically housebound by her inability to cope with real life. Dragging herself to an alumni gettogether, she comes into contact with her ex-best friend, a beauty called Elise who has left Michigan behind to become a budding starlet in Hollywood. Joyful reunion and corrosive obsession ensue, and Abby abandons her stagnant life to become a handmaiden to Elise, though her delusions about who exactly is saving whom have a hysterical undertow. Elise is too self-absorbed (and often too drunk) to see it, however, and as Abby gradually infiltrates and undermines her friend's life, relationships and career, resentments fester and rise and the tension builds - especially when an experimental director and his EST-like cult of creativity become part of the picture. When life imitates perfervid art, Abby proves a fantasist with a powerful sting. THOUGH FOR POTBOILERS, nothing comes close to TEMPER (Scout Press, $27), by Layne Fargo, a bodice-ripper set in the downtown Chicago theater world that also features a Svengali figure and the woman, or women, in his thrall. Chief among them is Kira Rascher, an actress with an Ava Gardner allure and the usual insecurity about being taken seriously. When the man of her stage set dreams - Malcolm Mercer, lead actor and artistic director of a high-concept, low-budget company - has her audition to be his co-star (against the wishes of his business partner and platonic roommate, Joanna Cuyler), she does what it takes to get the part. And then some. Like a black hole of charisma that crushes all in his orbit, Malcolm pushes his people to their boundaries and beyond, erasing the line between acting and being. There's violence here, but it's not only physical; it's emotional and psychological - even intellectual. And it leads exactly where you think it will. Mai gets what's coming to him, but the plot moves so quickly, and the breathing gets so heavy, even as you roll your eyes at the predictability of the denouement, you find that you've been sucked into the muck and you're wallowing there amid the words. When you finally climb out, though, and calm the heavy breathing, another realization may wash over you: The gender of their protagonists is not the only thing these books have in common. There's also a notable lack of tanks, nukes, scientifically engineered disease, computer viruses and other 21st-century weapons. These are low-tech nailbiters. In a world where we are increasingly obsessed with the tyranny and horrors of the small screens to which we are all teth-ered, the reminder that peril comes from all sorts of places and actual people may be the most thrilling development of all. VANESSA Friedman is the fashion director and chief fashion criticfor The Times. Women in these thrillers Eire as varied and unpredictable, as compelling and flawed, as women in the real world.

Copyright (c) The New York Times Company [June 2, 2019]

Review by Publisher's Weekly Review

In his first novel not centered on Hannibal Lecter in 44 years, bestseller Harris (The Silence of the Lambs) unveils a new villain, killer Hans-Peter Schneider, who rents a house in Miami Beach, Fla., that once belonged to Colombian drug kingpin Pablo Escobar in order to find the gold hidden beneath it. Cari Mora, a beautiful woman who survived a childhood as a conscript in FARC, the Colombian guerilla army, is the home's caretaker, and Schneider, to whom the "sound of a woman crying is... music" and who uses a liquid cremation machine to dispose of his prey, immediately regards her as a potential victim. When Schneider and Mora first meet, she catches a "whiff of brimstone off him." Few surprises mark the ensuing duel between the misogynistic sadist and the femme fatale, who learned certain skills from FARC that come in handy in their predictable showdown. The absence of Harris's usual superior storytelling will dismay fans, but the main problem is that Schneider doesn't come close to matching Lecter as a memorable monster. One can only hope for a return to form next time. Agent: Morton Janklow, Janklow & Nesbit Assoc. (May

(c) Copyright PWxyz, LLC. All rights reserved

Review by Kirkus Book Review

Morbid mysterian Harris (Hannibal Rising, 2006, etc.) returns with a trademark mix of murderous psychopaths and morally iffy good guys.Lesson No. 1: Don't mess with a determined Colombian woman, especially not one with combat experience and no fear of dying. The title character is a case in point: 25, pretty, though with scars that speak to a terrible past. Under the watchful eye of the immigration authorities, she works several jobs, including managing a luxurious Miami property with a murky title, a property that was once owned by drug lord Pablo Escobar and under which he tucked away a trove of gold ingots. Enter Hans-Peter Schneider, a decidedly nasty fellow in the tradition of other Harris villains. Hans-Peter has fangs with "silver in them that shows when he smiles" and is otherwise rather vampiric in aspect, and he has a thing for harvesting organs and selling women into slavery. He's after that gold, and Cari is a mere inconvenience to be dealt with in due time, minus a limb or two, perhaps. So it is with Cari's pool cleaner friend Antonio, anyway, who winds up an object of Hans-Peter's attention: "These were Antonio's legs. That was Antonio's torso. His head was missing." Things get ickier still as heads explode, bob around in liquid cremation machines, and otherwise undergo assorted unpleasantries. Hans-Peter isn't the only one after the gold, of course, and then there are the rising waters thanks to climate change, waters that have burrowed their way under the mansion. It's a race against timeand crocodiles, and all the other ways of dying unhappily in South Florida. It's vintage Harris, with nice twists and elegant ways of expressing just how bad bad people can be. Suffice it to say that, as the story winds to a blood-soaked close, some of the principals probably won't be showing up in a sequel.Refreshingly, entertainingly creepy and with nary a fava bean in sight. Copyright Kirkus Reviews, used with permission.

Copyright (c) Kirkus Reviews, used with permission.