Review by New York Times Review

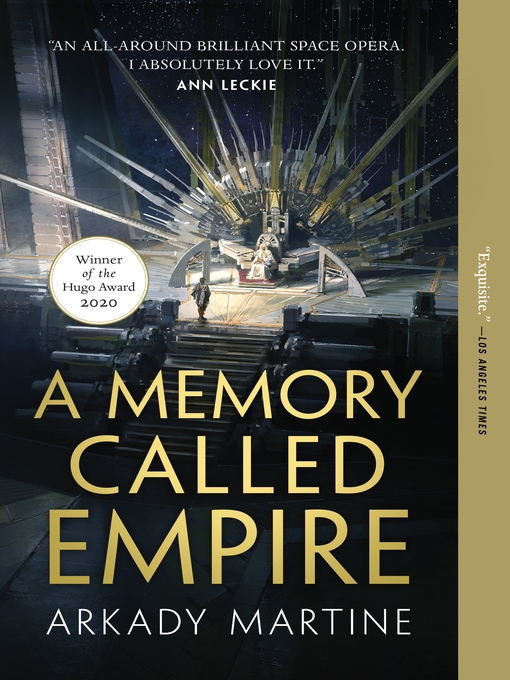

THE LAST FEW YEARS have seen an uptick in pop culture stories featuring time travel, from the repetitions and revisions of "The Good Place" and "Russian Doll" to developments in "Game of Thrones," "Star Trek: Discovery" and "Avengers: Endgame." Sometimes the MacGuffin by which we get to play with anachronism, but often also rooted in questions of free will and determinism, time travel is a fascinating springboard for fiction: Are there many futures, or just one? Can you change the past without changing the future, or yourself? This column brings together books about time fractured and out of joint, time as an unbroken lineage resisting empire, and time travel glimpsed through the overlapping lenses of psychology, philosophy and physics. Kameran Hurley's THE LIGHT BRIGADE (Saga, $26.99) is based on her 2015 short story of the same name, fleshing out the high-concept skeleton of a story about soldiers who are literally broken into light in order to teleport them to different theaters of war. Dietz lives in a bleak future where Earth's climate has been devastated, Mars colonized and governments replaced by corporations whose mergers and acquisitions are supported by standing armies. When the city of Säo Paulo disappears in an event called the Blink - causing more than two million people, including Dietz's family and friends, to vanish instantly - Dietz decides to help fight those responsible: the Martians. Or so she's told. But as Dietz is incorporated into the Light Brigade, something goes wrong. Her "drops" start landing her in places she isn't meant to be, with a different platoon full of people she doesn't know, but who seem to know her. Every drop is disorienting, but eventually Dietz understands that she's experiencing the war out of order, jumping back and forth within her own experience of it every time she's turned into light. And with every drop, she gains new perspective on who's fighting whom, and at what cost. "The Light Brigade" is passionately brutal, fierce and furious in voice and pace. Everything's appropriately grueling, from Dietz's memories of life before she joined her corporation to her fractured experiences of battle, ft's a particularly cinematic experience of war, "Full Metal Jacket" meets "Edge of Tomorrow," close up in the muck and blood and horror, ft's genuinely moving, too: all these heartbreaking young people caught up in a sick lie that everyone half-knows but can't look at directly. It was difficult at times to situate myself in the timeline and significance of Dietz's drops, especially early on when the only distinctions in the exhausting homogeneity of warfare are the casts of characters making up different platoons. But I'm hard pressed to consider that a flaw instead of a strength, especially when grim idealism is so much a part of Hurley's brand. And this is, at its core, an idealistic book, hope lurking somewhere beneath the hurt. Arkady Martine's A MEMORY CALLED EMPIRE (Tor, $25.99) is a mesmerizing debut, sharp as a knife that threatens as much by the gold filigree in its hilt as by the edge of its blade. Ambassador Mahit Dzmare - young, brilliant and lonely - has spent her life on Lsei Station enamored of the vast empire that borders it: Teixcalaan, a place of extravagant architecture and exquisite poetry celebrating, among other things, the empire's martial prowess. Lsei Station, by contrast, is austere and utilitarian, maintaining a tense independence from Teixcalaan partly through the careful machinations of the former ambassador Yskandr Aghavn. But Yskandr has mysteriously gone missing, and Mahit has been chosen to replace him, as much for her familiarity with Teixcalaanli language and literature as for her compatibility with Yskandr's "imago": a neural copy of him recorded 15 years earlier. Lsei Station survives in space through the secret technology of imago lines, grafting the memories, skills and personalities of the dead onto the living, integrating past and present into something new to take into Lsel's future. Mahit will carry a young Yskandr with her to help her navigate the City, Teixcalaan's capital. But when she arrives there, disaster strikes: When she learns Yskandr is dead, likely murdered, the Yskandr in her head shorts out in response, leaving her to sink or swim in the beautiful, implacable hostility of the Empire. "A Memory Called Empire" makes much of past and future selves, of memory and language and the things that can change them. One of the first questions Mahit asks her cultural liaison is, "How wide is the Teixcalaanli concept of 'you'?" - a question that roots philosophy in grammar, makes manifest how language and custom are indissociable from the politics of conquest. With incredible clarity and precision, Martine folds layer after layer of complexity into this book, such that it, like Mahit, is a fusion of Lsei Station and Teixcalaan: welding beauty and efficiency, building engineering out of verse, ft left me utterly dazzled. Kate Mascarenhas's THE PSYCHOLOGY OF TIME TRAVEL (Crooked Lane, $26.99) is an equally astonishing debut, simultaneously a science fiction novel, historical drama, lockedroom murder mystery and magnificent meditation on how human beings experience and adapt to mortality. Time travel is invented in 1967 by four women in Britain, nicknamed "the pioneers," and with it come rules: ft's impossible to travel to a time before the invention of time travel, or to change the future. Because of that, time travelers - whose profession develops mundanely enough to merit its own curious tax treatment - can, in fact, travel into the past or future and speak to different versions of themselves, to family members whose deaths they experienced, to children who haven't been born yet. But not all the pioneers get to be time travelers: One of them, Barbara, breaks down during a television broadcast that's supposed to publicize their triumph, and Margaret, the unspoken, aristocratic leader of the group, manipulates the others into cutting Barbara out of the project for her own good. Consequently Barbara is the only one of the pioneers to live her life in a straight line, leaving time shenanigans behind - until one day in 2017, when her granddaughter Ruby receives a court document from the future describing the impossible murder of an elderly woman. Ruby becomes convinced it's about Barbara; meanwhile, in 2018, a woman named Odette stumbles across the murder scene. From there, the story unfurls through different points of view in a moving arabesque crossing generations. Without shirking the mechanics of how time travel works, the novel dwells at length in how time travel feels, both for those who hop back and forth through it and for those who experience it linearly, ft observes that trauma is a kind of time travel, inasmuch as one is compelled to reexperience the same event; and explores what happens to grief when your dead parent is still alive in a past to which you have unimpeded access. Mascarenhas offers us a world in which time travel has affected art at least as much as geopolitics, in which time travelers develop their own sealed and vicious culture, full of cruel hazing calculated to cut out their empathy in self-defense. This is also a novel in which the rich lives of women are given center stage - helping and hurting and falling in love with each other, being, more than anything else, significant to each other, as enemies or lovers. Breathtakingly tender and wryly understated, "The Psychology of Time Travel" feels like an antidote to a great deal of reported (and even fictionalized) history, its excised women now finding their way back into the spotlight. Ted Chiang's EXHALATION (Knopf, $25.95) collects nine deeply beautiful stories (two original to the collection, the rest published over the last 14 years), many of which explore the material consequences of various kinds of time travel. (Chiang's 2002 novella, "Story of Your Life," inspired the Oscar-nominated 2016 movie "Arrival.") From the purely determined universe of "The Merchant and the Alchemist's Gate" to the parallel universes established with the push of a button in "Anxiety Is the Dizziness of Freedom," these stories are carefully curated into a conversation that comes full circle, after having traversed extraordinary terrain. In fact, each individual tale feels like its own conversation, several of them centered on discussions between intelligent people with different opinions exploring a difficult subject together. The longest piece, "The Lifecycle of Software Objects," is about people who invent childlike artificial intelligences called "digients" to sell as novelties - disconcertingly compared to pets throughout - and then refuse to give up the care of them when their popularity wanes and learning environments become obsolete. In addition to the patient clarity of the stories, there are notes to each one at the end of the book, adding an extra dimension to the collection; 1 loved learning the order in which the stories were written, how many of these notably contemporary-feeling pieces had their roots in discussions begun in the 1990s. Reading this book felt like being seated at dinner with a friend, one who will explain the state of the sciences to you without an ounce of condescension, making you a participant in the knowledge, ft is as generous as it is marvelous, and I'm left feeling nothing so much as grateful for it. AMAL EL-MOHTAR is a Hugo Award-winning writer and the author, with Max Gladstone, of "This Is How You Lose the Time War," forthcoming in July.

Copyright (c) The New York Times Company [June 9, 2019]

Review by Publisher's Weekly Review

Debut novelist Martine sets a careful course in this gorgeously crafted diplomatic space opera that strands its protagonist amid imperial politics and murder. Mahit Dzmare, summoned from tiny Lsel Station to replace the previous ambassador to the Teixcalaanli Empire, Yskandr, must negotiate both for Yskandr's corpse and for the safety of her home world, an object of Imperial annexation. Her fluency in Teixcalaanli language and culture ("for a barbarian") helps her decode the messages hidden in their poetry, even as it inclines her to the same starry-eyed admiration and involvement with the Imperial court that overcame her predecessor. Her secret implant of Yskandr's memories should be aiding her, but it is 15 years out of date and, apparently, sabotaged. Mahit instead relies on her need to establish an identity of her own while juggling an aging Emperor's desire for technological immortality and a threatened military uprising to his rule. The Teixcalaanli culture comes so fully to life that the glossary in the back of the book is unnecessary. Martine allows the backstory to unroll slowly, much as Mahit struggles with her intermittent memories, walking delicately upon the tightrope of intrigue and partisan battles in the streets to safely bring the tale to a poignantly true conclusion. Readers will eagerly await the planned sequels to this impressive debut. Agent: DongWon Song, Howard Morhaim Literary. (Mar.) © Copyright PWxyz, LLC. All rights reserved.

(c) Copyright PWxyz, LLC. All rights reserved

Review by School Library Journal Review

The Lsel Ambassador, Mahit Dzmare, arrives for her first assignment to Teixcalaan, only to discover that her predecessor is dead and the technology used on Lsel that could allow her to communicate with him is not working. It doesn't take her long to figure out that sabotage and murder are likely involved. With the help of her Teixcalaan Guide, Three Seagrass; some newfound allies; and her own abilities, Mahit navigates a political minefield. Revolution from within the Empire begins even as a new threat looms over her home of Lsel. Mahit must protect her home at all costs, in this complex world in which poetry is the language of history, culture, and communication. This is a complicated and dense space opera that may take teens some time to get into. But mature lovers of science fiction who are ready to make the jump from Robert Heinlein, Frank Herbert, or Andre Norton have much to enjoy here. VERDICT For avid sci-fi fans.-Connie Williams, Petaluma Public Library, CA © Copyright 2019. Library Journals LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Media Source, Inc. No redistribution permitted.

(c) Copyright Library Journals LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Media Source, Inc. No redistribution permitted.

Review by Kirkus Book Review

A scholar of Byzantine history brings all her knowledge of intricate political maneuvering to bear in her debut space opera.The fiercely independent space station of Lsel conserves the knowledge of its small population by recording the memory and personality of every valuable citizen in an imago machine and implanting it in a psychologically compatible person, melding the two personas into one. When the powerful empire of Teixcalaan demands a new ambassador, Lsel sends Mahit Dzmare, hastily integrated with an imago the current ambassador, Yskandr Aghavn, left behind on his last visit home, 15 years ago. Once arrived at the Empire's capital city-planet, the Jewel of the World, Mahit faces the double loss of Yskandr: Sabotage by her own people destroys the younger Yskandr copy within her, and she learns that the older original was murdered a few months ago. Bereft of the experienced knowledge of her predecessor, she will have to rely on all she knows of the sophisticated and complex Teixcalaanli society as she struggles to trace the actions that led Yskandr to his tragic end and to ensure Lsel's safety during a fierce and multistranded battle for the imperial succession. Martine offers a fascinating depiction of a civilization that uses poetry and literary allusion as propaganda and whose citizens bear lovely and sometimes-humorous names like Three Seagrass, Five Portico, and Six Helicopter but that can kill with a flower and possesses the military power to impose its delicately and dangerously mannered society across the galaxy. Love and sex are an integral aspect of and a thing apart from the nuanced and dangerous politicking. This is both an epic and a human story, successful in the mode of Ann Leckie and Yoon Ha Lee.A confident beginning with the promise of future installments that can't come quickly enough. Copyright Kirkus Reviews, used with permission.

Copyright (c) Kirkus Reviews, used with permission.