Review by New York Times Review

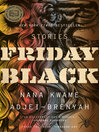

this year has been exhausting in so many ways, asking us to accept more than it seems we can, more than it seems should be possible. But really, in the end, today's harsh realities are not all that surprising for some of us - for people of color, or for people from marginalized communities - who have long since given up on being shocked or dismayed by the news, by what this or that administration will allow, what this or that police department will excuse, who will be exonerated, what this or that fellow American is willing to let be, either by contribution or complicity. All this is done in the name of white supremacy under the guise of patriotism and conservatism, to keep things as they are, favoring white people over every other citizen, because where's the incentive to give up privilege if you have it? Now more than ever I believe fiction can change minds, build empathy by asking readers to walk in others' shoes, and thereby contribute to real change. In "Friday Black," Nana Kwame AdjeiBrenyah has written a powerful and important and strange and beautiful collection of stories meant to be read right now, at the end of this year, as we inch ever closer to what feels like an inevitable phenomenal catastrophe or some other kind of radical change, for better or for worse. And when you can't believe what's happening in reality, there is no better time to suspend your disbelief and read and trust in a work of fiction - in what it can do. Adjei-Brenyah grew up in a suburb of New York and graduated with his M.F.A. from Syracuse University, where he was taught by the short story master George Saunders. "Friday Black" is an unbelievable debut, one that announces a new and necessary American voice. This is a dystopian story collection as full of violence as it is of heart. To achieve such an honest pairing of gore with tenderness is no small feat. The two stories that bookend the collection are the most gruesome, and maybe my favorites. Where they could be seen as gratuitous (at least to those readers who are not paying close attention to the news, or to those who intentionally avert their eyes), I find them perfectly paced narratives filled with crackling dialogue and a rewarding balance of tension and release. Violence is only gratuitous when it serves no purpose, and throughout "Friday Black" we are aware that the violence is crucially related to both what is happening in America now, and what happened in its bloody and brutal history. Adjei-Brenyah exaggerates only ever so slightly, or uses a futuristic hypothetical premise to reveal something true about this country's underhanded, undermining underbelly of an unconscious, which acts out its most base insults, impulses and injuries to the detriment of black communities (and many other communities of color). More often than not his characters struggle with not knowing what to do, given these seemingly impossible, extreme circumstances, and not all of them figure it out. But we don't need them to: His many truths, insights and beautifully crafted sentences just sing on the page. "All I do is sweat and feel hurt all around my body and in my head," says one character. "It gets dark. By then, I feel like death / poop"; another articulates, "How I feel about Marlene : She could keel over plus die and I'd be happy plus ecstatic." In smart, terse prose, Adjei-Brenyah is unflinching, and willing, in most of these 12 stories, to leave us without any apparent hope. But the hope is there - or if it isn't hope, it's maybe something better: levelheaded, compassionate protagonists, with just enough integrity and ambivalence that they never feel sentimental. Each of these individuals carries a subtle clarity about what matters most when nothing makes sense in these strange and brutal worlds he builds. The first story in the collection, "The Finkelstein 5," is about chain-saw decapitation, innocence destroyed by white privilege via brute force, and the lack of white accountability in our nation's maddening racial bias and failing justice system. The main character, Emmanuel, who throughout the story tempers his "blackness" on a l-to-10 scale, is trying to figure out how to exist in a society that expects you to play by rules it means to rule you with, unjustly. Does there come a time when enough is enough, and violence must face violence with violence? In "The Era," the author reveals a cold, sterile, prophetic world through the eyes of a teenager, Ben, who is not genetically modified, but a "clear-born." The story explores what humanity might look like in the future of scientific advancement, and what is true and authentic vs. syndicated or synthetic. Who is to say who is more valuable: the manmade beings or the "clear-borns"? Most compelling in this story is Ben's increasingly addictive relationship to a socially acceptable, regulated drug called "Good"; we eventually understand how cold and lifeless is the idea of gene manipulation technology if you follow it to its logical conclusion. "I look in the medical kit just in case. No Good. I take the empty injector and bring it to my neck. I hit the trigger and stab and hope maybe I'll get something. I hit the trigger again. Again." If Ben's voice borrows a little from Saunders's narrator in "The Semplica-Girl Diaries," the influence is understandable; I can think of no better short story writer to borrow from. That said, Adjei-Brenyah's voice here is as powerful and original as is Saunders's throughout "Tenth of December." The title of the collection is an inversion of our most bloodthirsty, capitalistic annual ritual - Black Friday - and in the titular story Adjei-Brenyah turns everything inside out to expose our blood and guts and desire and greed and savings. Every bit of hyperbole holds more truth than most of what the news, which only sometimes tries its best to be cool, calm and objective, has to report. Fiction in 2018 has gotten it right in finding truth without relying on fact. "Friday Black" explores capitalism and mall culture in a way I've never read before. It's one of the shorter entries in the collection, butit sets the gruesome scene for two later stories that tackle the same world from distinct points of view. All three mall stories are smart, funny and fun, despite having morbid tendencies. I could read a whole novel of voices from the many storefronts of this generic American Anywhere. The final story, "Through the Flash," is an intense and harrowing Groundhog Day journey through the possibilities of infinite time, and its potential implications for morality and redemption. At one point in the story, in which an infinitely looping reality means each day starts over again with a flash, the main character, Ama - a.k.a. "Knife Queen" - reflects on a particularly horrific period of time: "Every inch of my black skin painted the maroon of life." The word "maroon" here refers to blood, but I had to explore whether there were more meanings to unpack in it as well. Turns out it also means a firework, or a bang used to signal a warning, or, as a verb, to leave someone trapped and isolated in an inaccessible place, abandoned. Black Americans and other Americans of color are already carrying the weight of cruel, unreckoned-with histories on their shoulders; so to live amid unmitigated, too often racially motivated violence with little to no accountability on the horizon feels a lot like abandonment. Adjei-Brenyah, with his own "maroon of life," is here to signal a warning, or perhaps just to say this is what it feels like, in stories that move and breathe and explode on the page. The dystopian future "Friday Black" depicts - like all great dystopian fiction - is bleakly futuristic only on its surface. At its center, each story - sharp as a knife - points to right now. TOMMY orange is the author of "There There."

Copyright (c) The New York Times Company [July 21, 2019]

Review by Booklist Review

*Starred Review* Adjei-Brenyah's dozen stories are disturbingly spectacular, made even more so for what he does with magnifying and exposing the truth. At first read, the collection might register as speculative fiction, but current headlines unmasking racism, injustice, consumerism, and senseless violence prove to be clear inspirations. Adjei-Brenyah grabs immediate attention with The Finkelstein 5, in which a white man uses a chain saw to hack off the heads of five black children outside a South Carolina library. His acquittal sparks revenge attacks, eventually luring the story's protagonist, a teenager who works hard to keep his Blackness in the lowest digits on a 10-point scale, to further tragedy. Hate crimes become actual entertainment in Zimmer Land, in which clients pay for interactive justice engagement in a race-based-murder-theme-park. Friday Black exaggerates Black Friday shopping mania into a casual blood-sport, while shopping becomes a year-round battlefield in the related How to Sell a Jacket as Told by IceKing. A teen meets the twin fetuses his girlfriend aborted in Lark Street, and tortuous death and revival form a relentless cycle in Through the Flash. Ominous and threatening, Adjei-Brenyah's debut is a resonating wake-up call to redefine and reclaim what remains of our humanity.--Terry Hong Copyright 2018 Booklist

From Booklist, Copyright (c) American Library Association. Used with permission.

Review by Publisher's Weekly Review

Adjei-Brenyah dissects the dehumanizing effects of capitalism and racism in this debut collection of stingingly satirical stories. The arguments that exonerate a white man for brutally murdering five black children with a chainsaw in "The Finkelstein 5" highlight the absurdity of America's broken criminal justice system. "Zimmer Land" imagines a future entertainment park where players enter an augmented reality to hunt terrorists or shoot intruders played by minority actors. The title story is one of several set in a department store where the store's best salesman learns to translate the incomprehensible grunts of vicious, insatiable Black Friday shoppers. He returns in "How to Sell a Jacket as Told by IceKing" to be passed over for a promotion despite his impeccable record. Some stories take a narrower focus, such as "The Lion & the Spider," in which a high school senior has to take a demanding job to keep money flowing into his family's house after his father's disappearance. In "Light Spitter," a school shooting results in both the victim and gunman stuck in a shared purgatory. "Through the Flash" spins a dystopian Groundhog Day in which victims of an unexplained weapon relive a single day and resort to extreme violence to cope. Adjei-Brenyah has put readers on notice: his remarkable range, ingenious premises, and unflagging, momentous voice make this a first-rate collection. Agent: Meredith Kaffel Simonoff, DeFiore and Company. (Oct.) © Copyright PWxyz, LLC. All rights reserved.

(c) Copyright PWxyz, LLC. All rights reserved

Review by Library Journal Review

When asked in a New York Times Book Review interview why he writes political stories, Adjei-Brenyah answered, "If the house is on fire, I'm not going to write about what's in the fridge." In his smart, darkly funny debut collection of short stories, society itself seems on fire with racism, mob mentality, rampant consumerism, and the glorification of violence. Adjei-Brenyah sets the unflinching tone for the collection with the first story, "The Finkelstein 5," in which groups of vigilantes dole out their version of justice after a chainsaw-wielding white man is acquitted of murdering five black children outside a public library. In "Zimmer Land," a client can pay for the opportunity to commit a hate crime in a scenario disturbingly close to the 2012 killing of Trayvon Martin. In "Friday Black" and "How To Sell a Jacket as Told by IceKing," consumerism has become blood sport, and casualties are literally swept out of the way so the bargain hunting can continue unabated. The casual, conversational tone used by narrators -Corey Allen and Carra Patterson adds to the horror-the stories feel only slightly hyperbolic, even as they are completely unnerving. -VERDICT Brilliant and tragic, this is essential for all fiction collections. ["Powerful work for a wide range of readers": LJ 8/18 review of the Houghton Harcourt hc.]-Beth Farrell, -Cleveland State Univ. Law Lib. © Copyright 2019. Library Journals LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Media Source, Inc. No redistribution permitted.

(c) Copyright Library Journals LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Media Source, Inc. No redistribution permitted.

Review by Kirkus Book Review

Edgy humor and fierce imagery coexist in these stories with shrewd characterization and humane intelligence, inspired by volatile material sliced off the front pages.The state of race relations in post-millennial America haunts most of the stories in this debut collection. Yet Adjei-Brenyah brings to what pundits label our "ongoing racial dialogue" a deadpan style, an acerbic perspective, and a wicked imagination that collectively upend readers' expectations. "The Finkelstein 5," the opener, deals with the furor surrounding the murder trial of a white man claiming self-defense in slaughtering five black children with a chainsaw. The story is as prickly in its view toward black citizens seeking their own justice as it is pitiless toward white bigots pressing for an acquittal. An even more caustic companion story, "Zimmer Land," is told from the perspective of an African-American employee of a mythical theme park whose white patrons are encouraged to act out their fantasies of dispensing brutal justice to people of color they regard as threatening on sight, or "problem solving," as its mission statement calls it. Such dystopian motifs recur throughout the collection: "The Era," for example, identifies oppressive class divisions in a post-apocalyptic school district where self-esteem seems obtainable only through regular injections of a controlled substance called "Good." The title story, meanwhile, riotously reimagines holiday shopping as the blood-spattered zombie movie you sometimes fear it could be in real life. As alternately gaudy and bleak as such visions are, there's more in Adjei-Brenyah's quiver besides tough-minded satire, as exhibited in "The Lion the Spider," a tender coming-of-age story cleverly framed in the context of an African fable.Corrosive dispatches from the divided heart of America. Copyright Kirkus Reviews, used with permission.

Copyright (c) Kirkus Reviews, used with permission.