Review by New York Times Review

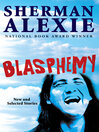

IN his 1936 essay "The Storyteller," Walter Benjamin drew a sharp distinction between prose fiction, meaning novels and short stories, and actual storytelling, meaning spoken narratives passed from one individual to another. The essential quality of storytelling, Benjamin wrote, is lived experience: "Every story contains, openly or covertly, something useful . . . a moral; some practical advice; a proverb or maxim. In every case the storyteller has counsel for his readers. But if today 'having counsel' has an old-fashioned ring, this is because the communicability of experience is decreasing. . . . We have no counsel either for ourselves or for others." Benjamin, of course, died long before the increased visibility of Native American literature, or the literature of any indigenous people with a living oral tradition, and so it's impossible (if a little entertaining) to imagine what he would make of Sherman Alexie. In one sense, Alexie is - and is well aware of being - the quintessential literary novelist, who, in Benjamin's terms, "has isolated himself, . . . is himself uncounseled and cannot counsel others. In the midst of life's fullness, and through the representation of this fullness, he gives evidence of the profound perplexity of the living." The stories in "Blasphemy," Alexie's collection of new and selected work, begin and nearly always end by reaffirming the brokenness, the dissonance and alienation of contemporary Native American life, usually delivered in withering punch lines: "On a reservation, Indian men who abandon their children are treated worse than white fathers who do the same thing. It's because white men have been doing that forever and Indian men have just learned how. That's how assimilation can work." Or: "When a reservation-raised Native American dies of alcoholism it should be considered death by natural causes." On the other hand, to understand Sherman Alexie as he often presents himself - as a clown, a cynic, a glib comedian, a blasphemer - is to miss the undercurrent of deep longing for the gravitas, the wisdom, of the storyteller. Although Alexie was not raised speaking a tribal language, and the loss of that language and the oral teachings associated with it comes up occasionally in his work, he peoples his fiction with characters who refuse to disguise or compromise their "Indianness," even if they can't quite define what Indianness means. In what is perhaps his best-known story, "This Is What It Means to Say Phoenix, Arizona" (which was adapted for the movie "Smoke Signals"), the young protagonist seeks out a former friend and eccentric outcast, Thomas Builds-the-Fire, for help transporting his estranged father's ashes back to his reservation. Thomas talks to himself, we're told, because even though he clearly has prophetic powers, he's "a storyteller that nobody wanted to listen to." But the protagonist knows enough to turn him when he feels "a sudden need for tradition," and Thomas provides him with a certain kind of offhand, cryptic spiritual guidance as they navigate the father's remains home, finally promising that he will take half the ashes and pour them into Spokane Falls: "Your father will rise like a salmon," he says, "leap over the bridge . . . and find his way home." Alexie's best stories bring the two sides of this literary persona - the embittered critic and the yearning dreamer - together in ways that are moving and extremely funny. "War Dances," a loose mosaic of lists, quizzes, interviews and poetry, evokes an entire spectrum of emotion surrounding the death of the narrator's father from alcoholism and diabetes: from rage to survivor's guilt to pure uninhibited grief to the blackest of black humor. ("If God really loved Indians," the father says, "he would have made us white people.") "The Toughest Indian in the World" arises out of an unexpected bond between a reporter and a prizefighter he picks up hitchhiking - in which the reporter's longing for an "authentic" Indian role model turns into an erotic encounter, which in turn becomes a kind of initiation: "I crawled naked into bed. I wondered if I was a warrior in this life and if I had been a warrior in a previous life. . . . The next morning, before sunrise, . . . I stepped onto the pavement, still warm from the previous day's sun. I started walking. In bare feet, I traveled upriver toward the place where I was born and will someday die." WHAT becomes clear, however, as the reader travels farther and farther upstream in this voluminous collection, is that Alexie's gifts have hardened and become reflexive over time. Alexie began writing in an era dominated by the dirty realists - the unholy trinity of Raymond Carver, Tobias Wolff and Richard Ford - and his work shares with theirs a certain bluntness and rawness, an aversion to sensory description, nuance or context, and an overriding interest in (some might say obsession with) male soUtude as a fount of life lessons. There's a tendency in Alexie's work to condense experience and biography into two- or three-sentence packages, and the result is that even stories with very different settings or plots tend to blur together: we feel constantly rushed from scene to scene, encounter to encounter, by a writer who's a little impatient with the texture of language and wants to get right to the point: "My Indian daddy, Marvin, died of stomach cancer when I was a baby. I never knew him, but I spent half of every summer on the Spokane Reservation with his mother and father, my grandparents. My mother wanted me to keep in touch with my tribal heritage, but mostly, I read spy novels to my grandfather and shopped garage sales and secondhand stores with my grandmother. I suppose, for many Indians, garage sales and trashy novels are highly traditional and sacred. . . . All told, I loved to visit but loved my home much more." The key phrase here, and throughout, is "All told" - as in, "I'm done with this part, let's move on." The effect of all this workmanlike prose is a desire to skim for the funny parts, which show up with great regularity, two or three to a page, like jokes in a sitcom script. The most disheartening aspect of this collection is the fact that, over 20 years, the jokes themselves haven't changed. Alexie's narrators and protagonists still see themselves as solitary outcasts on the margins of reservation life, and it shows: we hear a great deal about vodka, meth, commodity canned beef and horn-rimmed government glasses, but nothing about the intricacies of tribal politics, struggles over natural resources or efforts to preserve indigenous cultural life. Of course, a fiction writer follows the dictates of his own imagination, not any political or cultural agenda, but that's precisely the point: Alexie's world is a starkly limited one, and his characters' vision of Native America, despite their sometimes crippling nostalgia, is as self-consciously impoverished as it has ever been. What began as blasphemy could now just as easily be described as a kind of arrested development. Perhaps, willingly or not, that is the lesson he's trying to teach us. 'When a reservation-raised Native American dies of alcoholism,' Alexie writes, it's 'death by natural causes.' Jess Row is the author of two story collections, most recently "Nobody Ever Gets Lost."

Copyright (c) The New York Times Company [November 25, 2012]

Review by Booklist Review

*Starred Review* A poet and fiction writer for adults of all ages, National Book Award winner Alexie is a virtuoso of the short story. His first two blazing collections, The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven (1993) and The Toughest Indian in the World (2000), established him as an essential American voice. Now, many books later, best-selling Alexie has created a substantial, big-hearted, and potent collection that combines an equal number of new and selected stories to profound effect. In these comfort-zone-destroying tales, including the masterpiece, War Dances, his characters grapple with racism, damaging stereotypes, poverty, alcoholism, diabetes, and the tragic loss of languages and customs. Questions of authenticity and identity abound. In The Search Engine, a Spokane college student tries to understand a poet raised by a white couple who no longer writes because he fears that he isn't Indian enough. In the wrenching Cry, Cry, Cry, two cousins take very different paths toward being tribal, while in Emigration, a man who left the reservation trusts that his daughters will keep their tribe's spirit alive. Alexie writes with arresting perception in praise of marriage, in mockery of hypocrisy, and with concern for endangered truths and imperiled nature. He is mischievously and mordantly funny, scathingly forthright, deeply and universally compassionate, and wholly magnetizing. This is a must-have collection. HIGH-DEMAND BACKSTORY: As Alexie's creative adventurousness grows, so, too, does his popular acclaim. Expect his latest to raise the bar still further.--Seaman, Donna Copyright 2010 Booklist

From Booklist, Copyright (c) American Library Association. Used with permission.

Review by Publisher's Weekly Review

The National Book Award and PEN/Faulkner Award-winner's latest work combines 15 classics ("The Toughest Indian in the World"; "Salt"; "Indian Education") with 15 recent stories of varying length and tenor, and the result should attract new converts and invite back longtime fans. Heralded for his candid depictions of life on a reservation in the Pacific Northwest, versatile Alexie traverses familiar territory while also branching out. A son envisions his dead father's "impossibly small corpse" peering out of his morning omelet in the page-long "Breakfast." In "Gentrification," a white narrator's do-gooder intentions go predictably awry in his all-black neighborhood. "Night People" finds a sex-starved insomniac and a connection-hungry manicurist at a 24-hour New York City salon finding common ground in their loneliness and lack of sleep. In "Faith," a married man and a married woman at an evangelical dinner party who have an instantly easy rapport deliver witty repartee at the expense of their sheepish spouses. As in previous volumes, Alexie hammers away at ever-simmering issues, like racism, addiction, and infidelity, using a no-holds-barred approach and seamlessly shattering the boundary between character and reader. But while these glimpses into a harried and conflicted humanity prod our consciousness, there's plenty of bawdiness and Alexie's signature wicked humor throughout to balance out the weight. Agent: Nancy Stauffer Associates. (Oct.) (c) Copyright PWxyz, LLC. All rights reserved.

(c) Copyright PWxyz, LLC. All rights reserved

Review by Library Journal Review

This collection includes some of the best-known short pieces by Alexie (War Dances), along with a number of new stories. Loss, loyalty, dying fathers, basketball, Native Americans of the Pacific Northwest, and life on a reservation are themes repeated throughout. In "Whatever Happened to Frank Snake Church?" a man experiences a false vision of the death of his father and later, when grappling with real loss, tries to recapture his love of basketball. In "Breaking and Entering," a Native American man, misidentified as white, is vilified after fighting off an intruder in his home. The protagonist in "Gentrification" makes an enemy when he decides to remove a dirty mattress from the neighbor's sidewalk, while in "Old Growth," an accidental killing is awkwardly resolved. At times explicitly the subject of the story, as with "Indian Education," cultural identity is not always the dominant theme. For instance, "Do You Know Where I Am?" tells of a couple's courtship, life together and the lies they've told, while "Night People," features a New York manicurist who is watched at work for months from a nearby terrace. -VERDICT A large and diverse collection for fans of literary short stories. [See Prepub Alert, 4/30/12.]-John R. Cecil, Austin, TX (c) Copyright 2012. Library Journals LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Media Source, Inc. No redistribution permitted.

(c) Copyright Library Journals LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Media Source, Inc. No redistribution permitted.

Review by Kirkus Book Review

Sterling collection of short stories by Alexie (Ten Little Indians, 2003, etc.), a master of the form. The reader can take his or her pick of points where the blasphemy of Alexie's title occurs in this multifaceted assemblage, for there are several solid candidates. One falls about two-thirds of the way in, when a hard-boiled newspaper editor chews out a young Indian writer who might be Alexie's semblable. By that young man's count, the editor had used the word "Jesus" thrice in 15 seconds: "I wasn't a Christian and didn't know much about the definition of blasphemy," Alexie writes, "but it seemed like he'd committed some kind of sin." In Alexie's stories, someone is always committing some kind of sin, and often not particularly wittingly. One character, a bad drinker in need of help to bail out some prized pawned regalia, makes about as many errors as it's possible to make while still remaining a fundamentally decent person; another laments that once you start looking at your loved one as though he or she is a criminal, then the love is out the door. "It's logical," notes Alexie, matter-of-factly. Most of Alexie's characters in these stories--half selected and half new--are Indians, and then most of them Spokanes and other Indians of the Northwest; but within that broad categorization are endless variations and endless possibilities for misinterpretation, as when a Spokane encounters three mysterious Aleuts who sing him all the songs they're allowed to: "All the others are just for our people," which is to say, other Aleuts. Small wonder that when they vanish, no one knows where, why, or how. But ethnicity is not as central in some of Alexie's stories as in others; in one of the most affecting, the misunderstandings and attendant tragedies occur between humans and donkeys. The darkness of that tale is profound, even if it allows Alexie the opportunity to bring in his beloved basketball. Longtime readers will find the collection full of familiar themes and characters, but the newer pieces are full of surprises. Whether recent or from his earliest period, these pieces show Alexie at his best: as an interpreter and observer, always funny if sometimes angry, and someone, as a cop says of one of his characters, who doesn't "fit the profile of the neighborhood."]] Copyright Kirkus Reviews, used with permission.

Copyright (c) Kirkus Reviews, used with permission.