Review by New York Times Review

The United States remains the world's most powerful nation, Leslie Gelb says. LESLIE GELB recalls in this fluent, well-timed and sometimes provocative book that during the Jimmy Carter years, he privately implored his boss, Secretary of State Cyrus Vance, to give a speech demonstrating "that the administration did, in fact, have a foreign policy." To Gelb's distress, Vance replied, "Policy is baloney." Most presidents and secretaries of state wouldn't put it so bluntly, but history suggests that more than a few would privately side with Vance. Even presidents who start out with a distinct foreign policy strategy can find themselves overtaken by unexpected events or their own preoccupations. When Lyndon Johnson took office in 1963, he hoped to achieve a détente with the Soviet Union, but his insistence on prosecuting the war in Southeast Asia siphoned off so much of his international capital that by the end of his term, he was reduced to pleading with the Russians for a last-ditch summit meeting in Leningrad. (The answer was no.) George W. Bush in 2000 pledged a modest foreign policy, but after the 9/11 attacks he ordered the invasion of Afghanistan, raised the notion of pre-emption to a doctrine and ultimately used that declaration to justify a long, unpopular war in Iraq. Other presidents have gotten elected on deceptive promises that belie their private intentions or expectations. Dwight Eisenhower, one of the most honest men and sophisticated strategic thinkers ever to be president, bowed to the aggressive wing of the Republican Party and pledged while campaigning in 1952 to roll back Soviet Communism in Europe - although as the recent commander of Western forces on that continent, Ike of all people knew that this was a fantasy at the time. In 1960, John Kennedy vowed to increase defense spending in order to correct a Soviet "missile gap" that (as he had substantial reason to know) did not exist. Gelb, a former New York Times columnist and past president of the Council on Foreign Relations, persuasively argues that the most effective presidents try to fashion a coherent strategy, explain it forthrightly to the public and resist the temptation to be distracted by sudden opportunities and crises. Others have made this point before. (See, for instance, John Lewis Gaddis's landmark history "Strategies of Containment," which shows how six presidents fought the cold war.) But Gelb's treatment is distinctive, adorned with astute historical examples and reminiscences from his own high-level service in Johnson's Pentagon and Carter's State Department. It is filled with gritty, shrewd, specific advice on foreign policy ends and means that will be especially useful for a new president and secretary of state without deep experience dealing with the world (although the bulk of the book was clearly written before the world economic calamity of the past months). In the spring of 2009, as Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton make their first moves on the world's proscenium, Gelb's ruminations are welcome and stimulating. The author wishes to reclaim the middle ground in the debates over American foreign policy between the two parties, toward both of which he feels "a bit surly." At the start of his extended analysis of world power, he complains that "the core meaning of power has been lost, or even worse, hijacked by various liberals and conservatives," who "repeatedly corner our leaders into making commitments they cannot fulfill," as well as groups like "America's premature grave diggers" and "the world-is-flat globalization crowd," presumably led by Gelb's successor on the Times Op-Ed page, Thomas L. Friedman. Gelb insists that power "is what it always was - essentially the capacity to get people to do what they don't want to do, by pressure and coercion, using one's resources and position. . . . The world is not flat. . . . The shape of global power is decidedly pyramidal - with the United States alone at the top, a second tier of major countries (China, Japan, India, Russia, the United Kingdom, France, Germany and Brazil), and several tiers descending below. . . . Among all nations, only the United States is a true global power with global reach." One can learn much from Gelb's book without being persuaded by everything he writes. He shows special scorn for what Joseph Nye of Harvard has called "soft power." Gelb contends that "persuasion, good values and leadership won't - by themselves - cause foreign leaders to do your bidding. . . . To me, soft power is foreplay, not the real thing." This might understate the importance, for instance, of American support for the "good" Western values of human rights, democracy and market economics that emboldened millions of Eastern Europeans in 1989 to revolt against Soviet hegemony. Gelb may also underestimate both the value and the importance of mass citizen involvement in American foreign policy. For example, had Johnson trusted his exquisite political instincts and consulted a few more Americans outside the Eastern professional diplomatic establishment, he might have realized how unsustainable his war in Vietnam would turn out to be if he failed to win it cheaply and quickly. Gelb's chapter about domestic political influences on top foreign-policy makers is excellent on think tanks, cable TV and lobbies but does not discuss the mass influence of the Internet. (The chapter takes no serious note of blogs, except to mention that some think-tank analysts write them and to praise some bloggers for reading government documents.) In fact, future historians may well conclude that one of the most formidable forces in mobilizing opposition to George W. Bush's adventure in Iraq was the widely read liberal blog Daily Kos. Some readers may be surprised when Gelb praises the "genius" of Nixon and Henry Kissinger after Johnson's presidency, when "American power was drowning in Vietnam," in letting "the victim drown slowly while they steered the world's attention in another direction. . . . Whether by design or not, they dragged out the Vietnam War, perhaps hoping for victory, but not expecting one, and made their main focus the ushering in of the most active and wide-ranging period of high-wire, high-stakes diplomacy in American history." As a man sensitive to the complexities of political morality, Gelb might well have noted here that this interpretation of Nixon's approach may not seem quite so heroic to, for instance, the families of the tens of thousands of Americans who perished in Southeast Asia under Nixon's watch. None of this detracts from the general importance of Gelb's book. His plea for greater strategic thinking is absolutely right and necessary. The campaign of 2008 was but the latest instance of a presidential contest (like 1952 and 1964, to name only two) when the debate over foreign affairs was underdeveloped and the election mandate for the new president in foreign policy was strong but underdefined. That campaign and the months that followed have demonstrated that Barack Obama's inclination is to approach problems with a calm and steady concentration on long-term strategy. Thus, as he copes with domestic and world problems whose magnitude and range exceed those facing most American commanders in chief, he would no doubt benefit if someone should slip "Power Rules" into his evening reading. President Obama won't, by any means, concur with all of Gelb's meditations or policy recommendations, but he will surely agree that - especially in world affairs and especially at this moment - a president or secretary of state should consider strategy to be anything but baloney. Michael Beschloss is the author, most recently, of "Presidential Courage."

Copyright (c) The New York Times Company [October 27, 2009]

Review by Booklist Review

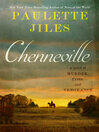

Jiles, author of the best-selling Stormy Weather (2007) and Enemy Women (2002), interweaves three narrative threads into a compelling post-Civil War tapestry. The stage is set for a tragic cultural collision when freed slave Britt Johnson a character firmly rooted in history and actual events travels west with his family and settles in frontier Texas. His dreams of a new life, however, are brutally shattered when his wife and children are abducted during a Kiowa-Comanche raid. Determined to reunite his family, the only circumstance he doesn't take into account is the assimilation of his children into Native American life. As the focus shifts back and forth between Johnson and the captives, Samuel Hammond, the newly appointed representative of the Office of Indian Affairs, serves as a deeply conflicted bridge between the two worlds. Jiles never reduces her cast of characters to stock stereotypes, tackling a traumatic and tragic episode in American history with sensitivity and assurance.--Flanagan, Margaret Copyright 2009 Booklist

From Booklist, Copyright (c) American Library Association. Used with permission.

Review by Publisher's Weekly Review

The author of Stormy Weather and Enemy Women returns with a lively exploration of revenge, dedication and betrayal set mainly in Kentucky and Texas near the end of the Civil War. Britt Johnson is a free black man traveling with a larger band of white settlers in search of a better life for his wife, Mary, and their children, despite the many perils of the journey itself. After a war party of 700 Comanche and Kiowa scalp, rape and murder many of the whites, Mary and her children get separated from Britt and become the property of a Native named Gonkon. Britt must wait through the winter before he can set out to rescue and reclaim his wife and children, only to discover that not only does he not have enough money to bargain with the Indians but also that his own family's fate has as much to do with land disputes and treaties as it does with his determination to get revenge. Jiles writes like she owns the frontier, and in this multifaceted, riveting and full of danger novel, she does. (Apr.) (c) Copyright PWxyz, LLC. All rights reserved

(c) Copyright PWxyz, LLC. All rights reserved

Review by Library Journal Review

As the Civil War winds down, freed slave Britt Johnson moves his wife and three children to Young County, TX. He dreams of starting a freight business, and his wife wants to teach school. But when the Comanche and Kiowa come raiding, Britt is not there to defend his family; his oldest son is killed, and the rest of his family and neighbors are taken captive. Britt spends a long winter plotting how to rescue them. Samuel Hammond, a Quaker man from Philadelphia, is sent to the region to be the new Indian Agent. He holds high ideals about nonviolence and teaching the Indians an agrarian lifestyle. Riveting suspense builds as Britt journeys north toward Indian country and encounters many Indian captives who do not want to be re-Anglicized. Using as her basis true histories of the Johnson family and others, Jiles (Stormy Weather) paints a stirring, panoramic tale of the young, troubled state of Texas. Highly recommended for historical fiction fans and readers who enjoy original Westerns. [Prepub Alert, LJ 12/08.]-Keddy Ann Outlaw, Harris Cty. P.L., Houston, TX (c) Copyright 2010. Library Journals LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Media Source, Inc. No redistribution permitted.

(c) Copyright Library Journals LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Media Source, Inc. No redistribution permitted.

Review by Kirkus Book Review

A novel of the Old West, based on the true story of Britt Johnson, a freed slave whose wife and family were stolen by Indians but eventually recovered. Most of Johnson's narrative has been passed down through oral history, but Jiles (Stormy Weather, 2007, etc.) fills in the gaps more than adequately. One day while Johnson is away getting supplies (and, sadly, after a nasty spat with his wife), his wife and two children are abducted by Kiowa-Comanche along with an older neighbor and her grandchildren. The Indians brutalize the women, but the childrenespecially the Johnson's ten-year-old son Jubebegin to adapt to life on the plains. The narrative divides itself between Johnson's search for his family and his family's exposure to Indian life, and then divides again with the introduction of Samuel Hammond, a Quaker who, as a representative of the postCivil War (and radically revamped) Office of Indian Affairs, is assigned the task of attempting to "civilize" the Comanche-Kiowa and turn a nomadic and warrior culture toward farming. Hammond is appalled at the number of abductions, and even more repelled to discover that some of the younger abductees have no desire to return to their previous lives. Part of the tension involves Hammond's growing discontent with Indian culturehe finds himself conflicted because, as a Quaker friend has written him, it is "our professed desire [as Quakers] to treat the Red Man as our brother and as a being deeply wronged over the centuries that we have inhabited this continent." Meanwhile, Johnson, in conjunction with his Comanche friend Tissoyo, succeeds in ransoming his wife and children, though he discovers that his wife has been psychologically scarred as well as physically injured. During her fragile recovery Johnson starts a freighting company, carrying goods from various settlements to frontier forts through dangerous territory. A rousing, character-driven tale. Copyright Kirkus Reviews, used with permission.

Copyright (c) Kirkus Reviews, used with permission.