Review by Booklist Review

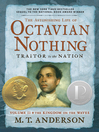

M. T. Anderson's books for young people reflect a remarkably broad mastery of genres, even as they defy neat classification. Any labeling requires lots of hyphens: space-travel satire ( Feed, 2002), retro-comic fantasy-adventure ( Whales on Stilts, 2005). This genre-labeling game seems particularly pointless with Anderson's latest novel, The Astonishing Life of Octavian Nothing, Traitor to the Nation (2006), an episodic, highly ambitious story, deeply rooted in eighteenth-century literary traditions, which examines, among many other things, pre-Revolutionary slavery in New England. The plot focuses on Octavian, a young black boy who recounts his youth in a Boston household of scientists and philosophers (The Novanglian College of Lucidity). The Collegians believe so thoroughly in the Age of Reason's principles that they address one another as numbers. Octavian soon learns that he and his mother are objects of one of the Collegians' experiments to learn whether Africans are a separate and distinct species. Octavian receives an education equal to any of the princes in Europe, until financial strains shatter Octavian's sheltered life of intellectual pursuits and the illusion that he is a free member of a utopian society. As political unrest in the colonies grows, Octavian experiences the increasing horrors of what it means to be a slave. The story's scope is immense, in both its technical challenges and underlying intellectual and moral questions--perhaps too immense to be contained in a traditional narrative (and, indeed, Anderson has already promised a second volume to continue the story). As in Meg Rosoff's Printz Award Book How I Live Now (2004), in which a large black circle replaces text to represent the indescribable, Anderson's novel substitutes visuals for words. Several pages show furious black quill-pen cross-hatchings, through which only a few words are visible, perhaps indicating that even with his scholarly vocabulary, Octavian can't find words to describe the vast evil that he has witnessed. Likewise, Anderson employs multiple viewpoints and formats--letters, newspaper clippings, scientific papers--pick up the story that Octavian is periodically unable to tell. Once acclimated to the novel's style, readers will marvel at Anderson's ability to maintain this high-wire act of elegant, archaic language and shifting voices, and they will appreciate the satiric scenes that gleefully lampoon the Collegians' more buffoonish experiments. Anderson's impressive historical research fixes the imagined College firmly within the facts of our country's own troubled history. The fluctuations between satire and somber realism, gothic fantasy and factual history will jar and disturb readers, creating a mood that echoes Octavian's unsettled time as well as our own. Anderson's book is both chaotic and highly accomplished, and, like Aidan Chambers' recent This Is All (2006), it demands rereading. Teens need not understand all the historical and literary allusions to connect with Octavian's torment or to debate the novel's questions, present in our country's founding documents, which move into today's urgent arguments about intellectual life; individual action; the influence of power and money, racism and privilege; and what patriotism, freedom, and citizenship mean. --Gillian Engberg Copyright 2006 Booklist

From Booklist, Copyright (c) American Library Association. Used with permission.

Review by Publisher's Weekly Review

Anderson (Whales on Stilts) once again shows the breadth of his talents with this stunningly well-researched novel (the first of two planned) centering on 16-year-old Octavian. The author does not reveal the boy's identity right away, so by the time readers learn that he is the son of an African princess, living a life of relative privilege and intense scrutiny among a group of rational philosophers in pre-Revolutionary War Boston, they can accept his achievements extraordinary for any teen, but especially for an African-American living at that time. These men teach him the violin, Latin and Greek. Anderson also reveals their strange quirks: the men go by numbers rather than names, and they weigh the food Octavian ingests, as well as his excrement. "It is ever the lot of children to accept their circumstances as universal, and their particularities as general," Octavian states by way of explanation. One day, at age eight, when he ventures into an off-limits room, Octavian learns he is the subject of his teachers' "zoological" study of Africans. Shortly thereafter, the philosophers' key benefactor drops out and new sponsors, led by Mr. Sharpe, follow a different agenda: they want to use Octavian to prove the inferiority of the African race. Mr. Sharpe also instigates the "Pox Party" of the title, during which the guests are inoculated with the smallpox virus, with disastrous results. Here the story, which had been told largely through Octavian's first-person narrative, advances through the letters of a Patriot volunteer, sending news to his sister of battle preparations against the British and about the talented African musician who's joined their company. As in Feed, Anderson pays careful attention to language, but teens may not find this work, written in 18th-century prose, quite as accessible. The construction of Octavian's story is also complex, but the message is straightforward, as Anderson clearly delineates the hypocrisy of the Patriots, who chafe at their own subjugation by British overlords but overlook the enslavement of people like Octavian. Ages 14-up. (Oct.) (c) Copyright PWxyz, LLC. All rights reserved

(c) Copyright PWxyz, LLC. All rights reserved

Review by School Library Journal Review

Gr 7 Up-Many readers think that classics have little relevance to our modern lives. But with the right author and the right turn on a classic tale, these stories can remain as relevant today as they were when they were first written. Julius Lester's Cupid (Harcourt, 2007) is a retelling of the ancient myth of the love story of Cupid and Psyche (originally written by Lucius Apuleius). Cupid, the Greek God of Love, and Psyche, a mortal princess, have a tempestuous love affair (and conflicts with Venus, Cupid's mother). Throughout their affair, Cupid and Psyche learn about themselves and the meaning of true love. With Jupiter's help, Psyche attains immortality. Lester's fresh and sassy prose brings new life and luster to the story, and actor Stephen McKinley Henderson's expert, enthralling narration always holds listeners' attention. On the other hand, M. T. Anderson's The Astonishing Life of Octavian Nothing (Candlewick, 2006), winner of the 2006 National Book Award, falls flat because its uniqueness renders it unintelligible. In this imitation of Voltaire's Candide, written in 18th-century language, young Octavian Nothing, an African child, is raised by tutors with numbers instead of names and subjected to experiments performed on him by Boston philosophers who seek to determine the intellectual ability of Africans. While the idea and the scope of Anderson's novel are fresh, the plot and the prose are so confusing that it becomes difficult to follow the story. The narration by actor Peter Francis James is first-rate, but only advanced high school students and aficionados of the Enlightenment will be able to wade through the novel. On the other hand, Lester's lively retelling of the Cupid classic enhances the original tale and makes it accessible to students.-Larry Cooperman, Seminole High School, Sanford, FL (c) Copyright 2010. Library Journals LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Media Source, Inc. No redistribution permitted.

(c) Copyright Library Journals LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Media Source, Inc. No redistribution permitted.

Review by Horn Book Review

(High School) A young slave, Octavian, grows up in Boston amongst a group of rationalist philosophers who treat him as a laboratory experiment in order to determine his capacity for reason. When political unrest in the colonies grows and his mother dies of smallpox, Octavian runs away and experiences firsthand the horrors of slavery and the hypocrisy of pre-Revolutionary America. Narrator James's precise elocution captures Anderson's eighteenth-century-styled prose, appropriately conveying the unique diction of each character. Some of the visual formatting of the book has been lost in the translation to audio, but Anderson's immense scope and incisive critique remain unblemished. The result is enthralling and wholly satisfying. (c) Copyright 2010. The Horn Book, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Media Source, Inc. No redistribution permitted. All rights reserved.

(c) Copyright The Horn Book, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Media Source, Inc. No redistribution permitted.

Review by Kirkus Book Review

A historical novel of prodigious scope, power and insight, set against the backdrop of the Revolutionary War. Readers are seduced by a gothic introduction to the child Octavian, whose bizarre situation is both lavish and eerie. Octavian is domiciled with a gentleman scholar at the "College of Lucidity." A sentient being, he is a living experiment, from his classical education to the notated measurement of his bodily intake and output; as such, the study will degenerate from earnest scholarly investigation to calculated sociopolitical propaganda. Upon learning that he's a slave, Octavian resolves to prove his excellence. But events force the destitute College to depend on a new benefactor who demands research that proves the inferiority of the black race. Like many Africans, Octavian runs away, joining the Revolutionary army, which fights for "liberty," while ironically never assuring slaves freedom. Written in a richly faithful 18th-century style, the revelations of Octavian's increasingly degraded circumstances slowly, horrifyingly unfold to the reader as they do to Octavian. The cover's gruesomely masked Octavian epitomizes a nation choking on its own hypocrisy. This is the Revolutionary War seen at its intersection with slavery through a disturbingly original lens. (Historical fiction. YA-adult) Copyright ©Kirkus Reviews, used with permission.

Copyright (c) Kirkus Reviews, used with permission.