Review by New York Times Review

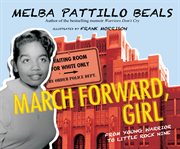

THE VERY EXISTENCE of Women's History Month is conflicted. It's a time to proudly recall the struggles and accomplishments of women long buried in our nation's narrative - but it also sets aside a single month out of 12 to celebrate half of the population, and therefore is a sort of insult. But four new books for young readers get it right, by highlighting the gender discrepancy in most tellings of the American story and seeking to fill in the gaps for a new generation. They offer supplemental histories that are also acts of unsilencing. An explicit narrative reclamation courses through ROSES AND RADICALS: The Epic Story of How American Women Won the Right to Vote (Viking, 160 pp., $19.99; ages 10 and up), by Susan Zimet. This book's supercharged introduction comes out of the gate swinging. "History is not what happened; it's the story someone tells us about what happened," the historian Sally Roesch Wagner writes in a foreword. "How did women gain a political voice? The old history told us male leaders gave it to us. Wrong. Amovement of women, assisted by their male allies, demanded and won it." These lines might also introduce votes FOR WOMEN: American Suffragists and the Battle for the Ballot (Algonquin, 320 pp., $19.95; ages 12 and up), by Winifred Conkling, which again offers a look back at the hard-fought right to vote. Unlike Zimet, whose writing pulses with a nerve rare for the subject, Conkling has composed something more like a lively textbook. Still, her approach is no less defiant. "Votes for Women" starts with the pivotal moment of success that came with Harry Burn's defining vote to ratify the 19th Amendment in 1920, then immediately zooms out. The fight for suffrage was won one day in the Tennessee statehouse, but it started nearly a century earlier, and that's where "Votes for Women" opts to begin, pulling back the curtain on 100 years of struggle. This larger story helps emphasize just how much of a footnote suffrage has been in our curriculum. The 19th Amendment is often treated as the accomplishment solely of sympathetic men, with paltry recognition of the women who fought for decades to lay the groundwork. Reading through both "Roses and Radicals" and "Votes for Women," I was struck by how little I had been taught about this crucial chapter of our history. These books turned me into a dispenser of feminist fun facts. "Did you know that Frederick Douglass spoke at the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848?" I asked a friend excitedly over happy hour. ("Yes," he replied. "But only because you already told me that last week.") In these books, the women who shaped the American narrative come to life with refreshing attention to detail. "Votes for Women" opens with a minibiography of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, set up as a cinematic hero's journey from that fateful moment when her father, mourning the death of his last son, told his daughter he wished she had been born a boy. Zimet is less wideeyed and more unsentimental in her approach. Opting for frankness about the racism of Stanton's platform, for instance, she contextualizes but also condemns her use of the atrocious term "Sambo." Of course, no women were more oppressed than women of color, and their stories are buried even deeper than those of the few celebrity suffragists who make it into stock history lessons. "Roses and Radicals" and "Votes for Women" both remind us of this fact through the inclusion of Sojourner Truth's 1851 "Ain't I a Woman" speech at a women's rights meeting in Akron, Ohio. "Truth was demanding that her listeners understand that women's rights weren't merely a matter for white women," Zimet writes. There are listeners today who still need help understanding this. Imagine if the most fundamental realities of women's intersecting identities were taken into consideration in history class. One woman of color in particular is at the center of Amy Hill Hearth's streetcar to JUSTICE: How Elizabeth Jennings Won the Right to Ride in New York (HarperCollins, 160 pp., $19.99; ages 8 to 12). In 1854, a century before Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery bus, there was Jennings's defiant bravery on a streetcar in the Five Points neighborhood of New York. Wrapped up in Hearth's detailing of Jennings's courage is a sobering recognition that the shame of our nation's history was widespread. Slavery wasn't restricted to the South. In fact, New York City itself was home to a municipal slave market until 1762. Writing with a compassionate handholding tone perhaps best suited for readers on the younger end of the book's suggested age range, Hearth reminds us that Jennings was not only blocked from riding in a streetcar, she also faced institutionalized obstacles. "For blacks, both boys and girls, the road to success was blocked by the color of their skin," she explains. "Only a very few managed to break through the barriers, and when they did, they still were not considered equal to whites." Things hadn't improved much nearly 100 years later, during the time that Melba Pattillo Beals writes about in her shocking autobiography, MARCH FORWARD, GIRL: From Young Warrior to Little Rock Nine (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 224 pp., $16.99; ages 10 and up). This book looks at Beals's younger years, before she was part of the Little Rock Nine who integrated Central High School (as she recounts in her best-selling "Warriors Don't Cry"). In empathetic yet unflinching prose respectful of younger readers, Beals depicts the nightmarish way the KKK held sway over the lives of black people. "The first thing I remember about being a person living in Little Rock, Ark., during the 1940s is the gut-wrenching fear in my heart and tummy that I was in danger," she begins. "By age 3, I realized the culture of this small town in the Deep South was such that the color of my skin framed the entire scope of my life." Beals candidly details the origins of her activism, as her fear transforms into rage over the passivity of the tormented adults who felt they could do nothing. There is in this new book even more untold history, more pain, outright terror and forgotten bravery, and yet so little has changed. It's thrilling to think of girls and young women immersed in not just history-book bullet points, but entire chapters fleshing out the stories of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Elizabeth Jennings. Previously, a curious child might have found these depictions in the pages of a dusty encyclopedia, and only if she knew where to look. We have been denied the full reality of our past, both its injustices and its secret heroes. It is still true that the road to success is blocked by both skin color and gender. Each victory in these pages is hung with the spoiler alert that we have yet to pass the Equal Rights Amendment. These books are an assertion of the female narrative, containing anger about the past, while arming a new generation with information they need to create a hopeful future. As Zimet writes in "Roses and Radicals," one thing is certain: "No matter what happens, the fight for women's rights continues." LAUREN DUCA is a columnist at Teen Vogue and has contributed to The New Yorker, The Nation and other publications.

Copyright (c) The New York Times Company [March 25, 2018]