Review by Booklist Review

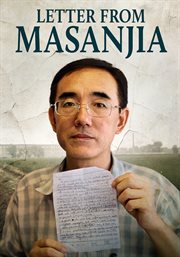

An intellectually exuberant, politically engaged student in Shanghai in the 1950s, Xu was a Communist but ran afoul of Maoist orthodoxy and was branded a Rightist and sentenced to imprisonment and hard labor in the Láodòng Gaizào (reform through labor) system. The next 14 years were a blur of prisons and work camps in western China, each bleaker than the last. He mined copper in damp caves, bore heavy loads up steep slopes, worked as a medical orderly giving fake injections, and sat shackled in solitary. His malnourished body deteriorated. Yet Xu remained generally adaptable and optimistic, learning what he could from his surroundings and enjoying brief camaraderie with other prisoners even as the seriousness of his original crime seemed to grow over time, and sudden execution remained a possibility. Xu's account of his escape through the desert into Mongolia is thrilling, yet this is ultimately less an adventure story than an act of historical witness, offering a rare and unflinching first-hand description of the cruelty of the Chinese gulag.--Driscoll, Brendan Copyright 2016 Booklist

From Booklist, Copyright (c) American Library Association. Used with permission.

Review by Publisher's Weekly Review

Swedish journalist and translator Hoh set out to write a novel about an escape from a Chinese labor camp, but in doing research stumbled upon something better: a real-life account of an escape that he could translate for a wider audience. The escapee was Xu Hongci (1933-2008), a committed Chinese Communist Party member. Born to a middle-class family during Japan's attempt "to liberate China from western imperialism," Xu grew up under Japanese occupation and witnessed the 1947 collapse of the alliance between the Communists and Kuomintang that caused China to descend into civil war. Xu joined the Party in 1948 and by the mid-1950s had a salary, a girlfriend, and a respectable position in the party. But when the openness of 1957's Hundred Flowers Campaign turned into the Anti-Rightist Campaign, Xu was branded a Rightist for his criticism and sentenced to six years of hard labor. Unable to bear the harsh labor camps, Xu made several unsuccessful escape attempts, and finally succeeded in 1972, becoming one of few escapees-perhaps the only one-of Mao's harshest prison. Xu recorded his story for a Chinese audience; Hoh helpfully contextualizes events to help Western readers absorb this extraordinary account of modern Chinese history. (Jan.) © Copyright PWxyz, LLC. All rights reserved.

(c) Copyright PWxyz, LLC. All rights reserved

Review by Library Journal Review

This wrenching first-person account reveals the ugliness and brutality of China's communist regime under Mao Zedong, through the human-scale lens of one individual's harrowing experience. As a young university student, Xu (1933-2008) was a loyal communist with an inconvenient streak of outspokenness and independent thought. Branded a Rightist after daring, naively and in good faith, to criticize party activities, Xu was sentenced in 1958 to six years in a labor camp, remained imprisoned as a "post-sentence detainee," and was resentenced in 1969 to 20 years' hard labor near the Burmese border. Against every probability, Xu broke out in 1972 and, despite the ravages of 14 years of physical and psychological torture, made his way on foot to Mongolia by way of his mother's home in Shanghai. Translator Hoh's notes provide sufficient historical context for readers lacking familiarity with modern Chinese history. With an impressive recall of names and details, the author shares dozens of intimate portraits of fellow prisoners and party cadres, and anecdotes of daily activities, all against the backdrop of systemic, mass-scale shortsightedness, cruelty, and denial of human rights. VERDICT A somewhat flat, matter-of-fact style and a slow start through Xu's days as a young student, shouldn't deter readers from this rare memoir. [See Prepub Alert, 7/18/16.]-Janet Ingraham Dwyer, State Lib. of Ohio, Columbus © Copyright 2016. Library Journals LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Media Source, Inc. No redistribution permitted.

(c) Copyright Library Journals LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Media Source, Inc. No redistribution permitted.

Review by Kirkus Book Review

An early victim of Mao Zedong's totalitarian regime is swept up in a time of terror."Under Mao Zedong's dictatorship," writes Xu, "the Chinese people had no human rights. My history is a good example of this." So it is. By this account, which seems to have enjoyed only modest success in its Chinese edition, Xu, born in 1933, was a loyal Communist cadre who had "personally experienced the injustice and darkness of the old society." Two events conspired to put him in the cross hairs: Nikita Khrushchev's secret speech denouncing Stalin's legacy in the Soviet Union and the Soviet invasion of Hungary, both of which furthered Mao's paranoia and inspired a program of constant purges. Running afoul of truer believers than he, Xu, a so-called class traitor, was sent to a labor camp in 1958, where he was beleaguered with the usual denunciations: "Your heinous crimes have caused great losses to the people!" Amazingly, he managed to escape, if only temporarily, and more than once. The path he charted each time was the most tortuous possible, intended to shake off pursuers. When, in 1972, he succeeded, he traveled from near the Burmese border to his mother's home in Shanghai, then crossed into Mongolia, where he lived for several years in exile until, after Mao's death, he thought it safe to return home. Xu's narrative is of interest as a survivor's account of the camps in those early years of the Anti-Rightist Campaign, which would precede a time of famine and then the Cultural Revolution. It is of less interest as an adventure yarn, for the narrative is rather flat, without the dramatic pacing of, say, Papillon or Slavomir Rawicz's genre-defining The Long Walk (1955). An often harrowing, valuable account for students of daily life in the early years of the period culminating in China's little-documented civil war of the 1970s. Copyright Kirkus Reviews, used with permission.

Copyright (c) Kirkus Reviews, used with permission.